For a tropical island, Clipperton doesn’t have very much going for it. The tiny, ring-shaped atoll lying 1,000 kilometres off the southwest coast of Mexico is covered in hard, pointy coral and a prodigious number of nasty little crabs. The wet season from May to October brings incessant and torrential rain, and for the rest of the year the island reeks of ammonia. The Pacific Ocean batters the island from all sides, picking away at the scab of land that rises abruptly from the seabed. A few coconut palms are virtually the only thing that the island boasts in the way of vegetation. Oh, and the sea all around is full of sharks. It isn’t much of a surprise that Clipperton Island is decidedly uninhabited. Over the course of the island’s modern history, four different nations—France, the United States, Britain, and Mexico—fought bitterly for ownership of Clipperton. It was desirable both for its strategic position and for its surface layer of guano, since the droppings of seabirds (as well as bats and seals) are prized as a fertiliser due to their high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus. Each of the four countries in turn attempted to maintain a permanent presence on Clipperton between 1858 and 1917. When a contingent of Mexican settlers did finally gain a toehold on the atoll, they were forgotten and left stranded on the island with a delusional man who seized the chance to become a dictator.

For a tropical island, Clipperton doesn’t have very much going for it. The tiny, ring-shaped atoll lying 1,000 kilometres off the southwest coast of Mexico is covered in hard, pointy coral and a prodigious number of nasty little crabs. The wet season from May to October brings incessant and torrential rain, and for the rest of the year the island reeks of ammonia. The Pacific Ocean batters the island from all sides, picking away at the scab of land that rises abruptly from the seabed. A few coconut palms are virtually the only thing that the island boasts in the way of vegetation. Oh, and the sea all around is full of sharks. It isn’t much of a surprise that Clipperton Island is decidedly uninhabited. Over the course of the island’s modern history, four different nations—France, the United States, Britain, and Mexico—fought bitterly for ownership of Clipperton. It was desirable both for its strategic position and for its surface layer of guano, since the droppings of seabirds (as well as bats and seals) are prized as a fertiliser due to their high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus. Each of the four countries in turn attempted to maintain a permanent presence on Clipperton between 1858 and 1917. When a contingent of Mexican settlers did finally gain a toehold on the atoll, they were forgotten and left stranded on the island with a delusional man who seized the chance to become a dictator.The island’s English name comes from a tenuous association with a British pirate, but the first modern explorers to claim Clipperton were the French, in 1858. Their intention was to land on the island’s shores and read out a proclamation, but this proved to be difficult; approaching the island with the ship posed a significant risk of running aground on the coral reef, and smaller rowboats were thwarted by sharks and fickle tides. Desperate, the French resorted to sailing around the perimeter of the island while reading the proclamation out to its coastline. Then, satisfied, they departed. Although they were aware of the guano, they felt it was likely to be of inferior quality, so they left it at that.

The next country to claim the island was the United States, in 1892. Unlike the French, the Americans suspected that Clipperton’s guano was extremely valuable, and they annexed the island under the auspices of the U.S. Guano Islands Act. A small crew of American miners spent the next few years on the island attempting to turn a profit, but poor market conditions and expensive resupply-trips intervened. Then, in 1897, the Mexicans decided they’d had enough of the United States occupying an island so close to the Mexico coast. A small group of Mexicans sailed over, lured two of the three Americans away, and left a Mexican flag in place of the American one that had been flying from a forty-foot pole. The U.S. backed off and gave up its claim to the island, but France and Mexico were unable to come to an agreement. To complicate matters, an English company then decided to try a guano-mining operation of their own, insisting that they did not care who owned the island. Mexico allowed them to proceed.

The British had high hopes, and got straight to work building a new settlement on Clipperton. They put up houses, constructed an enclosed soil garden, and planted more palms. But the island was pretty much as inhospitable as ever, and the mining, which began in 1899, did not prove to be lucrative. Although the Clipperton guano was of fairly good quality, there was now too much competition in the market for it to be worthwhile. By 1910 the British decided that the effort was futile, and removed all of their employees except for one island caretaker. The island’s other claimants, France and Mexico, signed an arbitration treaty leaving the question of Clipperton’s ownership to King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy. He began his deliberation.In the meantime, Mexico sent over a group of 13 men from their army to guard the island, including a de facto governor by the name of Ramón Arnaud. Wives and servants followed, and a number of children were born on the island in the early 1910s. An American ship was wrecked on the island in 1914; rescue came quickly, and the Americans advised the Mexicans to leave. Arnaud declined; all he did was expel the last remaining Brit from the island, sending the man and his family away with the Americans. With their last employee expelled, Britain stopped paying attention to Clipperton; meanwhile, Mexico was taking increasingly little notice of it themselves owing to a developing revolution in the country. Without any explanation, ships stopped arriving at Clipperton. The tiny community was dependent on the mainland for food and information, and soon their cache of supplies began to dwindle. In this case, no news was bad news.

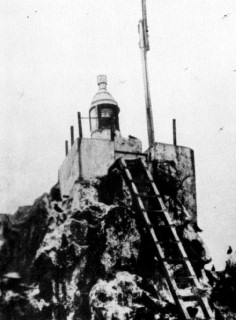

At this point there were approximately 26 people on Clipperton Island: 13 soldiers, about 12 women and children, and a reclusive lighthouse-keeper named Victoriano Álvarez who lived alone at the base of a sheer cliff below the lighthouse that the Mexicans had constructed in 1906. The island’s vegetable garden had been lost to the elements, and the only types of food available from the island itself were birds, bird eggs, and fish. There were also a few coconuts every week, but these were not a sufficient source of Vitamin C, and the islanders—especially the adult men—began getting sick with scurvy. One by one, they started dying; their fellow islanders buried their bodies deep beneath the sand in order to make them inaccessible to the crabs. Arnaud was mildly alarmed, but he was reluctant to abandon the island. At any rate, he knew that any attempt to reach the mainland would probably end badly; the one boat that the islanders owned did not have enough fuel for a trip over to Acapulco, and rowing it would be extremely difficult with only five men remaining on Clipperton, all of them suffering the effects of undernourishment and vitamin-deficiency.

The situation took another turn for the worse when Arnaud spied a distant ship, and talked the three other soldiers into joining him in the rowboat and going to the ship for help. Out on the water there was no sign of any such ship; it is quite possible that Arnaud had been deceived by an illusion. Angry, the three other soldiers attempted to overpower Arnaud and seize his weapon. Several of the wives watched helplessly from shore. The struggling mass of men fell overboard, and all of them drowned in the waves. Only hours later, two unrelated emergencies arose almost at once: a hurricane appeared offshore, and Arnaud’s heavily pregnant widow went into labour with the couple’s fourth child. The women and children took refuge in the cramped basement of the Arnauds’ house, and Alicia Rovira Arnaud gave birth to a son, Angel. Mother and baby survived, but the islanders emerged from the basement to find their buildings torn to pieces.

Just then, Álvarez the hitherto-unassuming lighthouse-keeper abruptly arrived at the destroyed settlement, collected the weapons, and threw them into the deep waters of the lagoon. Saving one rifle for himself, he announced to the women and children that he was now the king of the island. With that, he began a campaign of enslaving the women for whatever purposes he desired. One mother-daughter pair who refused to obey him were raped and shot to death. The rest were given regular beatings at the minimum.

Months passed, with Álvarez borrowing whichever female islander he wanted whenever he wanted: when he’d had enough of 20-year-old Altagracia Quiroz, he moved on to 13-year-old Rosalia Nava, and then 20-year-old Tirza Randon. The strong-willed Randon was far and away the most outspoken about her hatred of Álvarez, but was unable to think of a way to escape. “King” Álvarez was aware of the chance of being discovered by passing ships, especially since he knew that Alicia Rovira Arnaud would immediately tell all to any outsider who appeared. Consequently, Álvarez singled out Arnaud for threats, telling her that he would kill her the moment anyone from the outside world came into view.

Álvarez might have known full well what he was doing, but it is also possible that he was psychotic. He had been belittled for much of his life on account of his African heritage, which was as stigmatised in Mexico as it was in the United States at the time. Years of isolation on Clipperton could only have amplified his anguish; lighthouse-keeping was notorious for causing madness.

Somehow, life at the colony went on for nearly two years under Álvarez’s reign of terror. The women and children divided up the coconuts and the leftover scraps of materials following the storm. Álvarez went on cycling through his trio of women. In the middle of July 1917, he got tired of Tirza Randon again, and decided that his next target was Alicia Rovira Arnaud, whom he had not pursued earlier. He picked up his rifle, took Randon back to the main settlement, and informed Arnaud that she was to present herself at his hut by the lighthouse the following morning. Sensing an opportunity, Randon informed Arnaud, “Now is the time.”

On 18 July 1917, Arnaud and her seven-year-old son, Ramón Arnaud Jr., set out for the lighthouse-keeper’s hut, accompanied by Randon. Álvarez, sitting outside roasting a bird, was in uncharacteristically good spirits; however, he was not happy to see Tirza Randon back so soon. “What are you doing?” he asked her, and attempted to shoo her off. Instead, she ran into Álvarez’s hut, returned with a hammer, and upon a signal from Arnaud, took the hammer in both hands, swung, and struck Álvarez in the skull. And then a second time. Arnaud sent her son inside the hut, and meanwhile Álvarez shook off Randon, grabbed an axe, and went after Arnaud. Arnaud yelled to her son to get Álvarez’s rifle. He did, but in the meantime Randon had landed another good swing on Álvarez, and he fell to the ground. She had most likely killed him by this point, but she allowed her rage to lead her to a knife, return, and stab the body repeatedly. In hysterics, Randon then began slashing at the dead man’s face. The dictator of Clipperton Island had met his end.

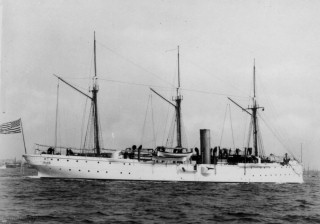

Even as the three still stood alongside the expired tyrant, little Ramón spotted something on the horizon that the community had not seen in nearly two years: a ship. The USS Yorktown was an American gunboat patrolling the west coast of North and South America, looking for German U-boats in accordance with a rumour that the Germans had established secret radio and submarine bases in the Pacific. Clipperton Island fell right along the Yorktown’s route, and certainly qualified as a potential hiding-place for the enemy.

The Yorktown circled Clipperton and made an attempt to send a smaller boat ashore, but the Americans were unable to reach the island and the boat returned to the ship. The islanders were devastated to see this retreat; just when they had caught sight of an opportunity to escape, it had disappeared. The women even briefly discussed whether they should just give up and either shoot each other or drown themselves in the lagoon. Fortunately, though, the Americans made a second attempt at sending their boat to Clipperton’s shores, and this time they were successful.

Arnaud met the Americans and frantically indicated the islanders’ desire to leave as soon as possible. Several members of the crew accompanied the women to the settlement in order to collect a few possessions, and others investigated the lighthouse. The Americans noted that the children were all small for their ages due to malnutrition; in particular, two-year-old Angel Arnaud was suffering from rickets and could not walk. Eleven-year-old Francisco Irra carried Angel on his back all the way to the American boat, and the sailors took the Clipperton Island survivors—three women and eight children—to the Yorktown. Álvarez’s body was left for the crabs.

Yorktown captain Commander Harlan Page Perrill later wrote in a letter to his wife:

I noted the women and some children gathering along the beach and you can imagine my surprise when the watchers on the bridge reported that they were getting into the boat. Speculation was rife. When Kerr got alongside and made his [oral] report, he revealed a tale of woe absolutely harrowing in its details.

Navigator Lieutenant Kerr’s official written report of the Clipperton Island rescue divulged no details whatsoever about the anti-social lighthouse-keeper; Kerr and Perrill were both eager to protect Randon and the other survivors from the potential legal and social repercussions of the final altercation between the women and Álvarez. For seventeen years, neither man would say a word about what had really happened on Clipperton Island between 1914 and 1917.

The Yorktown briefly suspended its German-hunting and set a course for Salina Cruz, Mexico, where a number of the women and children had family members. They sent ahead a wireless message to the British consulate in the city asking for help in locating relatives. The islanders all experienced some seasickness but liked the environment of the ship, and the sailors grew fond of the children. On 22 July 1917, the Yorktown reached the mainland. |

| Ramón-Arnaud y Alicia Rovira |

Right after the ship anchored, a boat appeared carrying Felix Rovira, the father of Alicia Rovira Arnaud. He had been regularly questioning Mexican authorities as to the fate of his daughter, only to have been told repeatedly – and erroneously – that all of the Clipperton Island colonists had died. Rovira and his daughter and four grandchildren had a reunion so moving that a number of the sailors burst into tears. A small fund that the crewmen had established to help the survivors start new lives on the mainland was turned over to them. The local citizens were deeply grateful to the Americans for the rescue, and threw a party at a local hotel for the sailors and the survivors.

Initially, Perrill had supposed Alicia Rovira Arnaud to be around forty years old. In reality, she was only twenty-nine, and the other women were several years younger. Nine years on Clipperton Island through an incredible gauntlet of hardships had taken their toll; however, eleven of the settlers had made it through. Their story was passed from person to person in subsequent years, and came to be known all over the west coast of Mexico.

Victor Emmanuel III of Italy finally made up his mind in 1931, awarding Clipperton Island to France. There have been occasional presences on the island since as the result of French/American military activities, scientific expeditions, and the occasional brief set of castaways. Ramón Arnaud Jr. even revisited the island with a team of biologists led by Jacques Cousteau in 1980; seventy-year-old Arnaud was pleased to see his place of birth in spite of the trauma. But no one has tried to live permanently on Clipperton since the last settlers were rescued by the Yorktown. Even without a crazed lighthouse-keeping rapist-tyrant, the island is very poorly equipped for comfortable human habitation.A lot of micronations, some of them not so serious, claim the Clipperton Island as a part of its territory.

Victor Emmanuel III of Italy finally made up his mind in 1931, awarding Clipperton Island to France. There have been occasional presences on the island since as the result of French/American military activities, scientific expeditions, and the occasional brief set of castaways. Ramón Arnaud Jr. even revisited the island with a team of biologists led by Jacques Cousteau in 1980; seventy-year-old Arnaud was pleased to see his place of birth in spite of the trauma. But no one has tried to live permanently on Clipperton since the last settlers were rescued by the Yorktown. Even without a crazed lighthouse-keeping rapist-tyrant, the island is very poorly equipped for comfortable human habitation.A lot of micronations, some of them not so serious, claim the Clipperton Island as a part of its territory.Amateur radio DX-peditions

The island has long been an attractive destination for amateur radio groups, due to its remoteness, difficulty of landing, permit requirements, romantic history, and interesting environment. While some radio operation was done ancillary to other expeditions, major DX-peditions include FO0XB (1978), FO0XX (1985), FO0CI (1992), FO0AAA (2000), and TX5C (2008).

The island has long been an attractive destination for amateur radio groups, due to its remoteness, difficulty of landing, permit requirements, romantic history, and interesting environment. While some radio operation was done ancillary to other expeditions, major DX-peditions include FO0XB (1978), FO0XX (1985), FO0CI (1992), FO0AAA (2000), and TX5C (2008).One DX-pedition was the Cordell Expedition in March 2013 using the callsign TX5K, organized and led by Robert Schmieder. The project combined radio operations with selected scientific investigations. The team of 24 radio operators made more than 114,000 contacts, breaking the previous record of 75,000. The activity included extensive operation on 6 metres, including EME (Earth–Moon–Earth communication or 'moonbounce') contacts. A notable accomplishment was the use of DXA, a real-time satellite-based online graphic radio log web page that allowed anyone anywhere with a browser to see the radio activity. Scientific work carried out during the expedition included the first collection and identification of foraminifera, and extensive aerial imaging of the island using kite-borne cameras. The team included two scientists from the French-Polynesian University of Tahitiand a TV crew from the French documentary television series Thalassa.

An April 2015 DXpedition using callsign TX5P was conducted by Alain Duchauchoy, F6BFH, concurrent with the Passion 2015 scientific expedition to Clipperton Island, and engaging in research of Mexican use of the island during the early 1900s.

En 2015, l'expédition scientifique internationale PASSION 2015 a invité le député du Tarn Philippe Folliot à se joindre à elle. En effet, le géographe Christian Jost, responsable de l'expédition, a invité le député à joindre les autres chercheurs dans leur mission sur l'île. Philippe Folliot alors missionné par la ministre française des Outre-mer, George Pau-Langevin, devenait ainsi le premier élu de la République française à poser le pied sur l'atoll.

En 2015, l'expédition scientifique internationale PASSION 2015 a invité le député du Tarn Philippe Folliot à se joindre à elle. En effet, le géographe Christian Jost, responsable de l'expédition, a invité le député à joindre les autres chercheurs dans leur mission sur l'île. Philippe Folliot alors missionné par la ministre française des Outre-mer, George Pau-Langevin, devenait ainsi le premier élu de la République française à poser le pied sur l'atoll. |

| TOM ELLIOTT, wrote Clipperton: The Island of Lost Toys and Other Treasures |

No comments:

Post a Comment